The Myth of Modern Appliances – and How Wirecutter Gets It Wrong

by William Scheckel

I may enjoy summer mornings more than most people. My wife is a teacher and avid baker – AND she gets up a lot earlier than I do. In the summer when she has off, I wake up to the smell of a fresh pie being baked in our Thermowell – the built-in slow cooker in our 1953 Chambers stove. That pie can sit in there all day, cooking with the gas off so the retained heat slowly brings out the maximum flavor of the fresh berries and fruit in that day’s pie while retaining the moisture and warmth. Four, five, even 8 hours later we can take it out and eat it for dessert and it’s perfect. She’s a good baker,  but the flavor that Thermowell brings out in food is second to none. As I stand there making my coffee, it’s hard to not just pull it out and devour it, but I know the hours of retained heat cooking will make it even better. So off I go every day, waiting to eat my dessert that night while I work on restoring more of these remarkable appliances so even more families get to enjoy their beautiful design and unequaled performance.

but the flavor that Thermowell brings out in food is second to none. As I stand there making my coffee, it’s hard to not just pull it out and devour it, but I know the hours of retained heat cooking will make it even better. So off I go every day, waiting to eat my dessert that night while I work on restoring more of these remarkable appliances so even more families get to enjoy their beautiful design and unequaled performance.

Looking out at a room filled with a hundred or so of these, I’m puzzled as to why Wirecutter recently published two stories that advise people how to make their modern appliances last longer while also disparaging vintage appliances that have withstood the test of time.

The author, Rachel Wharton, states that she “wondered whether the culprit [behind the short lifespan of a modern appliance] was planned obsolescence …. Yet after a six-month investigation, [she] found a much more complicated answer.” It’s not really complicated, though: what it took her six months to find are the *reasons* for this planned obsolescence.

If you’re unfamiliar with the term, ‘planned obsolescence’ basically means that something breaks because it was designed to eventually break. The bottom line of her argument is that it’s not the manufacturer’s fault that they are forced to design lousy appliances that break – they don’t have any other choice because of the many reasons she’s happy to list: regulations, “people’s lust for new things,” price wars, technology and so on. She doesn’t come right out and tell us to call it “forced obsolescence” instead of “planned obsolescence,” but that is her point. I’m not convinced that would make her argument any better, though.

Vintage Appliances are No Fluke

What really undermines her articles is her allegation that we believe modern appliances don’t last long because we’re comparing them with vintage appliances that are still around – BUT, she claims, the old ones never lasted that long to begin with. She calls it “the myth of the 30-year-old fridge.” She claims an expert on appliances told her that appliances “never” lasted 30 years and that the average lifespan was “only 10 to 15 years.” She quotes one modern washing machine engineer who claims “No one talks about the other 4.5 million that didn’t last that long.” When I read things like this while surrounded by some of the best appliances America ever built – all of which are between 70 and 125 years old, I try to hold on to the sweet smells of dessert baking in my 70+ year-old stove at home instead of wondering how experts like that manage to get quoted in Wirecutter. And to be clear, those “other 4.5 million” appliances are still lingering in kitchens, garages, and basement “summer kitchens” all over the country. Every restorer I know turns away far more appliances than they can ever take in because of the flood of these so-called “outliers” – and more pop up in our inboxes every single day.

Seriously, I can’t imagine how any expert would believe that the 90-year-old stove or 70-year-old refrigerator in Grandma’s basement is a fluke. Vintage appliances from before the 1960s are the result of remarkably sophisticated engineering by some of the country’s best manufacturers and designers. Visionaries like John Chambers, O’Keefe & Merritt, Frank Alvah Parsons and Norman Bel Geddes left an indelible mark on American manufacturing and our kitchens. They made parts out of solid brass, cast iron, aluminum, and steel. They were built to last – and they have.

Repair vs. Landfill

Those old manufacturers took care to ensure each piece of these appliances could be replaced or repaired at any point in the future. These days, when a stovetop burner won’t light or the refrigerator won’t cool, you need to track down a new circuit board – if one even exists. And since modern manufacturers are opposed to your right to repair what you own, you end up stuck with a big piece of junk for the landfill.

Those old manufacturers took care to ensure each piece of these appliances could be replaced or repaired at any point in the future. These days, when a stovetop burner won’t light or the refrigerator won’t cool, you need to track down a new circuit board – if one even exists. And since modern manufacturers are opposed to your right to repair what you own, you end up stuck with a big piece of junk for the landfill.

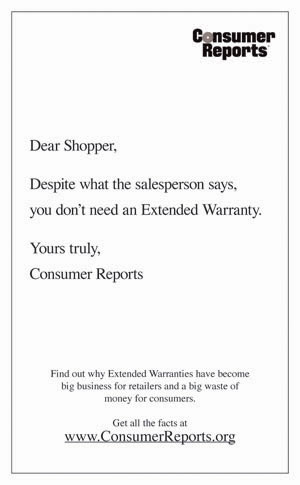

Ms. Wharton thinks repair issues are solved by buying an extended warranty – an expense that is so widely regarded as a terrible idea that Consumer Reports has been advising people against them since 2006. That year they took out a full-page ad in USA Today calling them a “big waste of money” and they’ve been repeating the message ever since.

A much more reliable way to ensure you can repair an appliance is by choosing one that has parts readily available – and that’s a vintage appliance. Often you can repair the part that’s broken, but if it needs to be replaced, there’s a robust industry of vintage appliance parts driven by the restorers who keep all these great machines alive, as well as the wide availability of parts stoves and refrigerators all over the country.

Vintage Appliances are Far More Efficient

People like to talk about how efficient modern appliances are without really thinking about what real efficiency is. My 1953 Chambers stove is the result of 40 years of efficiency engineering that had as its primary goal being able to cook with the gas off. Heat retention in a Chambers is so good that once you get the oven or built-in slow cooker to temperature, you can turn the gas off and let it cook for hours. Because the oven seal is machined cast iron and not a flimsy piece of rubber, the moisture is locked in, too. They used to advertise with bits about preparing dinner in the morning, turning the gas off before you leave for the day and then coming home to a warm, moist meal. They even made a commercial about it as far back as 1926 and made a cookbook that teaches you how to do it. We cook on retained heat pretty much every day in our home and all these decades later it still works perfectly. That’s real efficiency, and no modern brand can even approach that.

People like to talk about how efficient modern appliances are without really thinking about what real efficiency is. My 1953 Chambers stove is the result of 40 years of efficiency engineering that had as its primary goal being able to cook with the gas off. Heat retention in a Chambers is so good that once you get the oven or built-in slow cooker to temperature, you can turn the gas off and let it cook for hours. Because the oven seal is machined cast iron and not a flimsy piece of rubber, the moisture is locked in, too. They used to advertise with bits about preparing dinner in the morning, turning the gas off before you leave for the day and then coming home to a warm, moist meal. They even made a commercial about it as far back as 1926 and made a cookbook that teaches you how to do it. We cook on retained heat pretty much every day in our home and all these decades later it still works perfectly. That’s real efficiency, and no modern brand can even approach that.

Since refrigerators are not my expertise, I asked fellow restorer Jules Tatum in Charlottesville, VA if he had conducted bench tests on his vintage refrigerators. He told me that his research makes it clear that there’s no contest. “These fridges are better insulated and have thicker walls, so they hold the temperature better. Vintage compressors use less power because of the quality of the materials and the efficiency of the design.”

“What makes a modern fridge even less efficient is that it has at least one defrost circuit, two fans, motors, light bulbs and so on that are all huge power draws,” Tatum explains. “Modern fridges have to cycle on and off much more frequently.”

When diving into this subject, I have come across tests that claim vintage fridges only draw 30% as much power as a modern fridge, while others say up to 50%. It usually depends on the exact size and features being compared. Either way, once you calculate in the fact that thousands of these are still running 70+ years later, the true measure of their efficiency is obvious. We can’t discount thousands of vintage appliances simply because they were scrapped because they were “old”.

Some will claim that modern ones are bigger – and yes, many are, but they sure as heck aren’t that much bigger! So, unless you’re running multiple vintage refrigerators at the same time, you’ll spend less operating a vintage fridge compared with a modern one.

Vintage Features Still Impress

Some argue that “modern appliances have all these features!” And I say “that’s when the problems started!” Even Ms Wharton agrees that “Any feature adds a layer of complexity to an appliance and makes it more susceptible to breaking.” It’s even item #1 on her list of how to get modern appliances to last – eliminate unnecessary features. But then she then writes in favor of a lot of these features that cause appliances to break anyway.

If you work on enough of these old appliances, you start to see a sharp decline in quality towards the late 1950s. By the 1960s, post-War consumerism pushed for less expensive appliances with “modern” or so-called “space age” features. This is when they had to sacrifice the quality of the materials to keep prices low. It was the price we paid for keeping up with the Joneses.

But not all features mean an appliance is low quality because not all features drain power or over-complicate the mechanism. When I show people the pop-up adjustable broiler or built-in slow cooker in a Chambers or the ultra-low simmer, large integrated griddle, and pull-down cover of an O’Keefe and Merrit, the response is universally “why don’t we still have stoves like this?!?”

Well, we do. They’re vintage stoves. And considering that they are reliable, often beautiful, made in America, efficient and durable, it’s puzzling that Wirecutter would take a stance against them.

A restored refrigerator from the same period in the same kitchen not only makes for a stunning look, but ensures your home appliances are efficient and long lasting. And as for that extended warranty? In a hundred years when your grandchildren have an issue with the restored vintage stove they inherited, they can give me a call.

William Scheckel is the owner of Chambers Rescue, a vintage gas stove restoration company located in Clifton, NJ. He specializes in the restoration of gas stoves of all brands made before 1960, with a particular focus on the legendary Chambers brand stoves. You can find out more about his work and these stoves at www.ChambersRescue.com